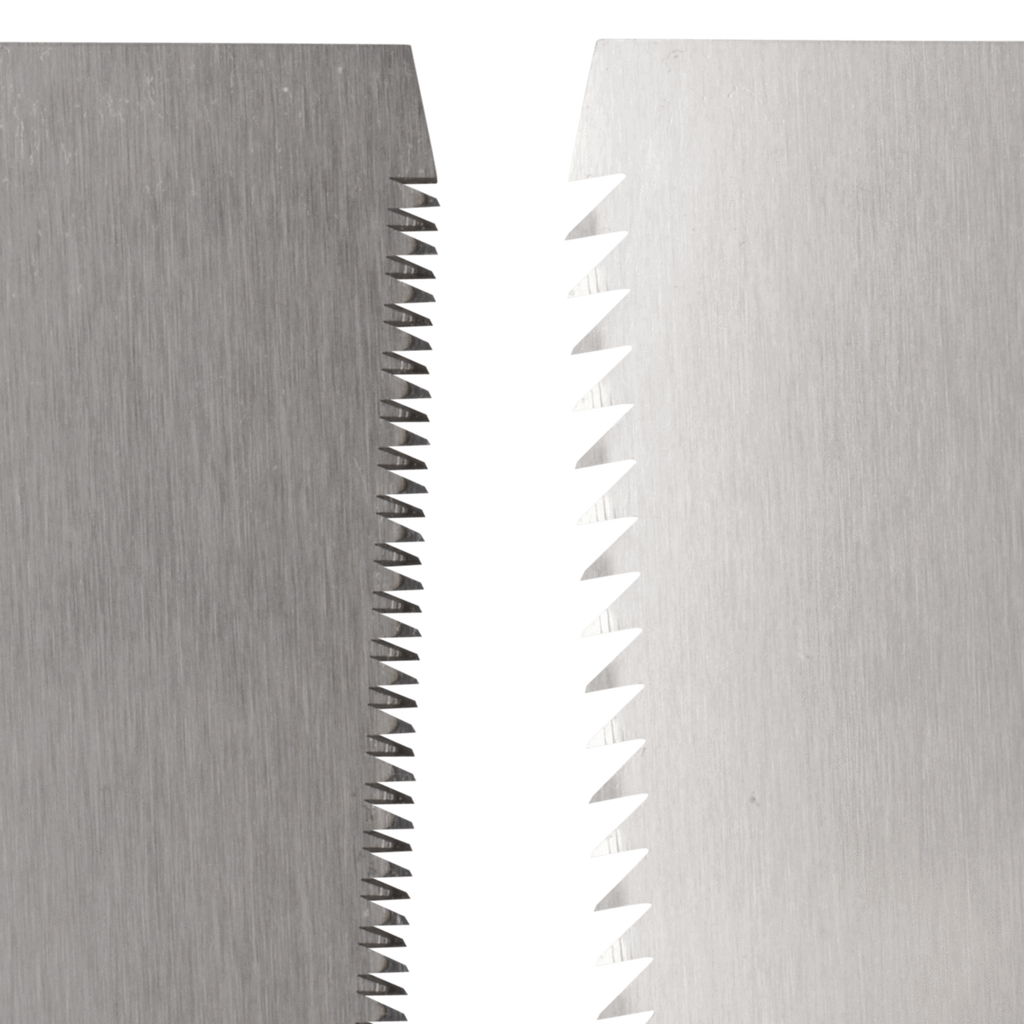

Japanese saws are distinctive from western hand saws in a few crucial ways, most of which rely on the fact that they cut on the pull-stroke. Since the blade of the saw cuts as it is drawn towards the user, rather than as it is pushed away, the blade is constantly in tension while cutting. This means that the saw plate can be made of very thin metal, even for saws designed to rip boards. In turn, because these saws leave a fine kerf, they remove less material as they cut and therefore are extremely efficient, requiring less effort and time compared to a similarly sized Western counterpart with a greater blade thickness.

The sizing of teeth in Japanese saws is generally proportional to the size of the saw itself. A larger saw usually means a larger tooth pattern, meaning a saw can cut faster and more aggressively, but the finish it leaves will be rougher. The smaller a Japanese saw is, the finer the teeth, which are capable of leaving extremely fine surfaces, but require more strokes to achieve the same cut. Japanese saw teeth are also graduated along the saw blade — often, the teeth closest to the handle are smaller and finer than the teeth farthest away, which are intentionally larger. This allows the user to start the cut with the fine teeth and progress to the more aggressive teeth once a kerf has been established.

A noteworthy exemption to this rule is our range of Silky saws. Silky has chosen to adopt the Western method of manufacturing uniform teeth on their sawblades, and offering different saws with finer or more aggressive tooth sizings in the same overall length. Click here to view our Silky saws.

Pull saws in the Japanese tradition range widely in use and specialisation.

The Ryoba Saw

The ryoba saw is prized by Japanese carpenters for its versatility, as it combines two specialised functions into one highly capable tool. Ryoba blades feature two teeth patterns on either edge of the blade — one set for cross-cutting across the grain of timber, and the other for rip-cutting with the grain. A Ryoba saw can be used to rip a board to the desired width with one edge and cut it to length with the other, or pressed into service on larger joinery if required.

If you are considering a first purchase of a Japanese saw, we recommend the Ryoba style as being the most capable of handling whatever is thrown at it, whether in the workshop or on a job site. The absence of a spine makes the ryoba appropriate for deep cuts or ripping, and the sawplate and teeth are quite tough and robust. We find that once a woodworker has tried this workhorse of a tool, it is destined to become part of a growing collection of Japanese saws.

The Dozuki Saw

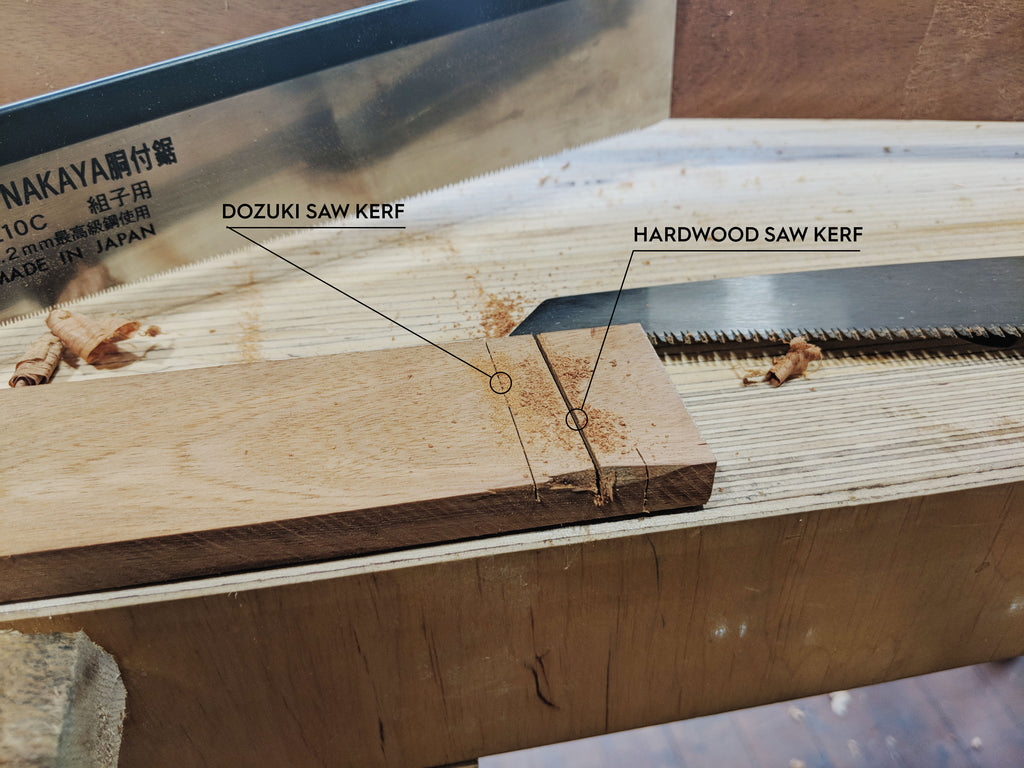

The dozuki pattern of saw is a specialised saw for joinery and fine cuts. The word dozuki in Japanese refers to a tenon shoulder, and it is from this saw’s specialisation that it takes its name. Dozuki saws use extremely fine blades and their teeth are given very minimal set, meaning that they barely protrude past the side of the saw plate. Because the blade is so extremely fine a dozuki saw uses a steel or brass spine as reinforcement, and is capable of cuts only as deep as the distance from the teeth to the spine.

Given the thinness of these blades, dozuki saws are ideal for fine work and the surface they leave does not require refinishing with either a chisel or plane. With a little practice, they are capable of following extremely precise lines and excel at detailed joinery, whether for dovetails, tenons, or any of the more specialised Japanese joints Western woodworkers are continually discovering.

A dozuki saw depends on its owner using a sawing motion that moves both directly forward and directly back, exactly parallel to the desired cut. If any left/right twist is introduced into the user’s action, the teeth of the saw may give way as they are driven into a quantity of timber they are not capable of removing. A lost tooth will not generally affect the performance of the saw greatly, but a greater strain will be placed on the tooth behind it as it is required to do the work of two teeth instead of one, and this tooth may also fatigue and detach.

As such, though they are capable of cuts beyond compare, Dozuki saws should be used with patience and care in order to maximise their lifespan. If you are familiar with Japanese saws and are able to follow a line with a Ryoba or Kataba style saw, you should have little difficulty and will certainly enjoy using a Dozuki. And, if worse comes to worse, we offer replacement blades for all of our saws so that you can get back to making cuts with less hassle and fewer profanities.

The Kataba Saw

Kataba saws are literally any type of saw that has teeth on only one side of the saw plate and strictly speaking this category includes spined Dozuki saws. However, we choose to separate the two, as the uses of the non-spined Kataba are more similar to the Ryoba.

Instead of incorporating both cross- and rip-cut teeth, the Kataba includes only one set. The advantage here is most easily felt when ripping long boards. Though the Ryoba employs a perfectly good set of rip teeth, the more heavily set cross-cut teeth eventually have to travel through the thinner kerf of the rip-cut teeth, and are prone to scratching the previously clean surface.

Kataba style saws eliminate this problem by shedding one set of teeth and specialising as either a robust cross-cut saw or a rip-cut saw, capable of ripping boards to width while leaving unmarred smooth surfaces.

Flush Cut Saws

Perhaps the most widely adopted Japanese saw in the West, the flush-cut saw is named for its function. By cutting teeth with zero set into a ductile, bendable blade, Japanese saw makers were able to invent the perfect tool for removing excess material protruding through completed joints. Through-tenons, dowels, wooden nails and plugs are easily trimmed to the height of the surrounding surface without damaging it.